Experts say coronavirus attacks on the brain are more common than thought

London — Rebecca Wrixon knew that working as a nanny for a pair of doctors could leave her exposed to the coronavirus, but as a healthy 44-year-old with young children, she didn’t worry much about catching COVID-19. It was already clear then, in early April, that the disease hit the elderly and those with underlying conditions hard, but it didn’t seem much of a threat to her healthy family.

Then one morning just after Easter, Wrixon woke up with a numb arm. She never had a cough or fever, never lost her sense of taste or smell, and it would take doctors days to even diagnose COVID-19 — and much longer to figure out how to stop her body’s reaction to it. The insidious disease quietly caused her body to attack itself, inflaming her brain, paralyzing half of her body, rendering her unable to see or speak, and almost killing her in the process.

Researchers in Britain now believe COVID-19 may hit many more people with similar neurological symptoms than commonly thought — including younger patients and those who, like Wrixon, never experience the most well-known signs of the disease. The fear is not only that these symptoms can be dangerous in themselves, but that they can linger, and nobody knows yet for how long.

“No normal symptoms”

Courtesy of Rebecca Wrixon

Wrixon’s 11-year-old daughter was in bed with a fever for about a day in early April, then Wrixon herself experienced some pain in her chest and a light rash, but she never suspected it was the coronavirus.

“I had no normal symptoms like they tell you to look out for at all. I just didn’t feel well, and just had itching around my chest and an ache from my chest, but no cough. No problems breathing or anything like that,” and then it all cleared up, she told CBS News from her home on England’s southern coast.

“It wasn’t until the Tuesday of the Easter holiday that I woke up and my arm was numb.”

When her husband came downstairs and found her struggling to operate the TV remote, she told him she couldn’t feel her arm, or her foot. Wrixon and her husband both thought the same thing.

Her husband asked her to state their daughter’s birthday and a couple other basic facts.

“I couldn’t answer. Didn’t have a clue,” Wrixon recalled. “So that’s when we were like, ‘I’m having a stroke.'”

They called an ambulance and she was rushed into the emergency room.

“Thought I was going to die.”

“She looked like she’d had a stroke,” said Dr. Ashwin Pinto, the consultant neurologist who ended up wrestling with Wrixon’s case for almost three weeks. “Really soon after I saw Rebecca, she was really beginning to struggle with her speech.”

Coronavirus, he said, “really wasn’t on the radar at all.”

But tests quickly confirmed there never was a stroke. Over the next few days, as Wrixon’s condition deteriorated precipitously and the magnitude of the pandemic started to register around Europe, she was tested for COVID-19 as a matter of course.

“I didn’t think, particularly, that it was going to be positive,” Pinto said.

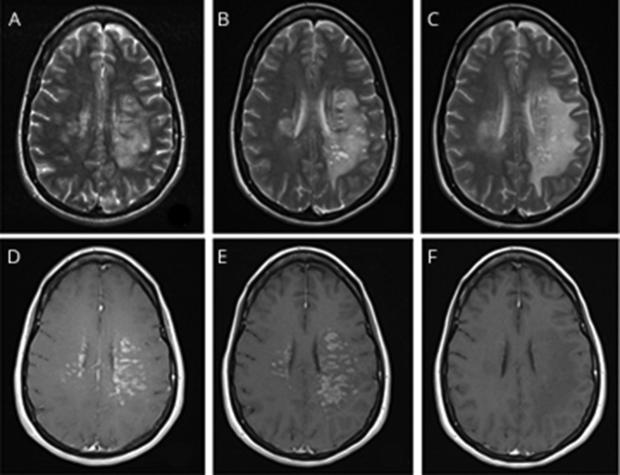

The result surprised him. Despite the positive throat swab test, however, there was nothing in Wrixon’s blood or spinal fluid to suggest the virus was directly attacking her central nervous system. But something was. MRI scans showed more than half of her brain severely inflamed.

American Academy of Neurology/University Hospital Southampton

At this point, Wrixon couldn’t move half of her body at all. She couldn’t see clearly and she couldn’t communicate with her doctors or her husband.

As leading neurologists grasped to understand what was wrong, Wrixon’s husband got no guarantees. His daughter asked him to promise that mom was going to come back home. He told her the doctors were doing their best, but he couldn’t promise anything.

“I thought I was going to die. I literally thought, ‘no, you’re not coming out,'” Wrixon told CBS News.

Courtesy of Rebecca Wrixon

Dr. Pinto was aware of just one or two cases outside the U.K. that looked similar, at least on paper. He’d read a study about a patient in Detroit whose autoimmune response to a COVID-19 infection had caused a similar, serious inflammation of the brain, so he decided to take a gamble and treat Wrixon not for a viral infection, but for an immune system run amok.

Once the COVID-19 infection had passed and she had tested negative for the virus, Pinto started giving Wrixon high dose steroids and blood plasma exchange. The exchange is meant to remove enough of a patient’s plasma — the part of the blood that carries antibodies tasked with fighting an infection — and replace it with a protein from donors whose immune systems aren’t overreacting to anything, to stop the body’s response and ease the inflammation.

It worked.

“As soon as the plasma exchange started, the next day I woke up and I moved my first finger,” Wrixon said. After five days of the treatment, she stood up again. “I was moving around. Literally, that plasma exchange works a miracle.”

After more than two harrowing weeks in the hospital she went home, and has since made a full recovery, almost. Three months later, Wrixon still gets pain and numbness in her hand, and sometimes she struggles to get her words out.

A “concerning increase”

How long those effects might linger, along with the overall prevalence of neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients, continues to worry Dr. Pinto, and he’s not alone.

Two recent British studies make it clear that while it’s better understood than ever, the new coronavirus is still guarding secrets.

A study published on July 8 in the neurology journal Brain found that of 43 patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infections, 12 suffered inflammation of the central nervous system, including the brain. Of those 12, one made a full recovery, 10 made partial recoveries, and one died.

COVID-19 infection, “is associated with a wide spectrum of neurological syndromes,” the study authors concluded. They called it “striking” to note, in particular, the “high incidence of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis” (ADEM is widespread inflammation in the brain and spinal cord) in the patients.

The study conducted at University College London’s National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery noted also that, as Wrixon discovered, the severe inflammation, “was not related to the severity of the respiratory COVID-19 disease.”

According to University College London, the neurologists behind the research said they would typically treat about one adult patient per month with ADEM, “but that increased to at least one per week during the study period (which coincided with the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in London), which the researchers say is a concerning increase.”

A larger study published in The Lancet, which includes the data from the UCL research, looked more broadly at the prevalence of neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients. It “identified a large proportion of cases of acute alteration in mental status, comprising neurological syndromic diagnoses such as encephalopathy and encephalitis and primary psychiatric syndromic diagnoses, such as psychosis.”

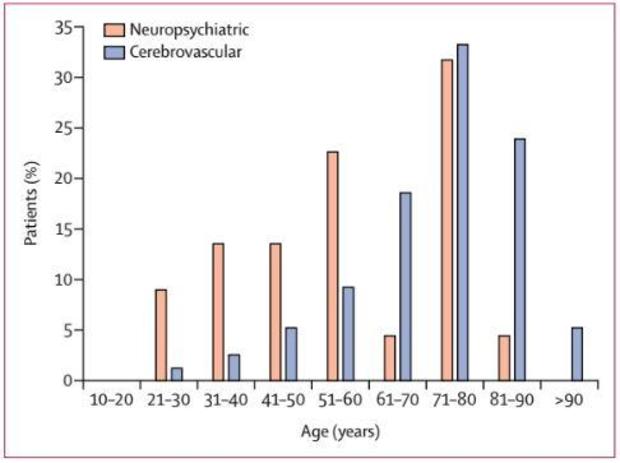

The study found that among 125 coronavirus patients, 62% “presented with a cerebrovascular event [stroke], of whom 57 (74%) had an ischaemic stroke, nine (12%) an intracerebral haemorrhage, and one (1%) CNS vasculitis [inflammation of blood vessels in brain or spine].”

It’s understood that COVID-19 patients, young and old but particularly older people, often experience strokes, but the researchers were surprised by the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in younger patients who (again, like Wrixon) do not suffer strokes. In the graph below, “cerebrovascular” indicates patients in the study who experienced strokes, whereas “neuropsychiatric” refers to patients with other cognitive and physical symptoms, and it shows the clear shift as age increases.

The Lancet

Any illness affecting the central nervous system can have long-term health implications, as millions of stroke survivors can attest. Viruses, from the common flu to the “Spanish Flu” that wreaked global havoc between 1918 and 1920, often leave their mark on survivors by damaging the brain.

Dr. Pinto pointed out that in the decade or so after the 1918 pandemic, doctors saw a surge in cases of a neurological illness called encephalitis lethargica, suspected by many to be a delayed response to the virus.

“If you follow movies, that’s the movie, ‘Awakenings,’ with Robert DeNeiro — it’s all about those patients who recovered from the 1918-1920 pandemic,” he said. “So we know that viruses have been associated with a lot of long-term brain risk.”

“What we really, really don’t know with coronavirus is what that will look like,” said Pinto. “We’re going to see this played out in real time.”

“This is not influenza”

“There’s so many people out there that are still thinking it’s the flu, and in fairness, before I got ill, that’s what I was thinking,” Wrixon told CBS News. “But now? Yeah, no way would I want anybody to go through what I went through.”

“Having to be in hospital on your own and not having any family or friends allowed to see you or visit you or speak to you, yeah, I wouldn’t want anybody to have to go through that at all.”

“This is not influenza,” stressed Dr. Pinto. “We have small influenza outbreaks in every country in the world, seasonal, in winter… We documentedly have not seen the range of terrible complications we get with this virus.”

Wrixon said it was hard now to see images on the news of people gathering in big groups, often without wearing masks.

“It’s ridiculous, really, that people aren’t looking at it more seriously.”

Click here to read the full academic study on Wrixon’s case.